Sake kasu, or sake lees, are the solids separated from the liquid after pressing the fermented mash in sake production. Since sake lees alone contain 8-12% abv of alcohol, it has frequently been used as a base ingredient for making shochu.

Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association | JSS

Sake kasu, or sake lees, are the solids separated from the liquid after pressing the fermented mash in sake production. Since sake lees alone contain 8-12% abv of alcohol, it has frequently been used as a base ingredient for making shochu.

Up until the 20th century, sweet potato and rice shochu were only produced and consumed locally in southern Kyushu. On the other hand, sake kasu shochu was produced by sake breweries as a supplementary business throughout Japan, excluding the Tohoku and Hokkaido regions.

Sake kasu shochu was not just a casual drink or cooking ingredient. Due to its high alcohol content, it also served as a disinfectant and other medicinal purposes. In addition, this type of shochu also became an ingredient for mirin, as well as in sake production. When added to the mash at the end of the fermentation process, it increases the alcohol content, preventing spoilage of sake.

Sake kasu shochu making also contributed to the local cycle of agriculture and the industry. After making shochu, the alcohol-free yet nutrient-rich lees became a great fertilizer for rice fields. This then enriched the soil to cultivate more rice. The rice then was used to make sake, and then from sake lees to shochu and fertilizers again. In northern Kyushu in particular, sake lees shochu production thrived to make the fertilizer for the rice field.

The close ties to the local agricultural practices gave this shochu a sacred status. In northern Kyushu, shochu often served as a feature in farming-related Shinto rituals, such as festivals after rice planting.

There are two main types of sake kasu shochu: kasu-tori and Kasu-moromi-tori Shochu.

Kasu-tori is the type of shochu made by distilling paste-like sake lees. It is also the centuries-old traditional method practiced in northern Kyushu and Shimane Prefecture.

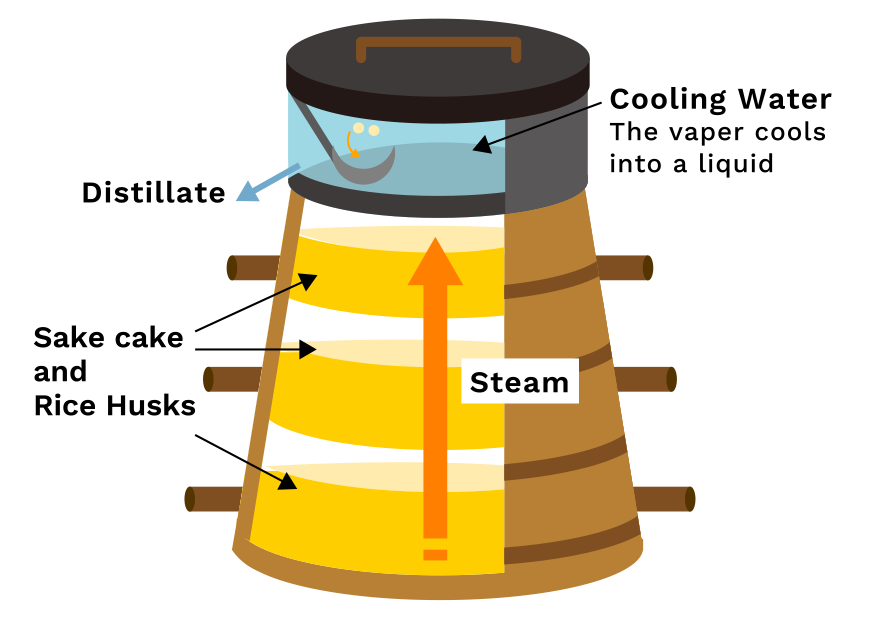

Traditionally, the method involves mixing sake with a small amount of water to make a paste-like mixture. The mixture then sits for several months and ferments with the yeast remaining in the lees. This brings up the alcohol content by 2-3%. Makers then add rice husks to the fermented mix and spread it on a basket. Next, this basket is set in a special wooden basket steamer with a device that collects the distillate. The rice husks help the steam pass through the lees mixture.

Today, makers have developed a method for making kasu-tori shochu with modern distillation techniques. Instead of fermenting lees and using a steam still, distillers break down fresh sake lees into small pieces. These pieces then undergo distillation using a reduced pressure still.

The rice husks and the wooden steamer basket contribute to the distinct flavor of traditional kasu-tori shochu. The husks provide a sweet, dried grass-like aroma while the basket adds a hint of wood. However, the fresh distillate is quite pungent. As a result, distilleries usually let it age for some time until the flavor mellows. Modern kasu-tori shochu has a fruitier flavor with a hint of sake-like aroma, without the grassy, woody notes.

Kasu-tori shochu is often served Mixed with chilled water or On the rocks. People also use it as a base to make Umeshu with steeped plums and sugar.

Mixed with chilled water

On the rocks

Umeshu

The method to make kasu-moromi-tori shochu differs slightly from kasu-tori shochu. Rather than a paste-like mixture, distillers dilute the sake lees with water to make a porridge-like mash (moromi). The mash then ferments for about two weeks. It is then distilled in either an atmospheric or a reduced pressure still. Some sake brewers use a mixture of their sake mash and sake lees to make this type of shochu.

Kasu-moromi-tori shochu has a milder flavor compared to the traditional kasu-tori shochu. Notably, the flavor usually mirrors the characteristics of the sake producing the lees. If the lees resulted from a ginjo type of sake, the shochu often has a fruity, floral aroma like ginjo sake.

Kasu-moromi-tori Shochu is often served Mixed with chilled water or On the rocks.

Mixed with chilled water

On the rocks